HOUSING INSIGHT SERIES

Delivering more affordable, quality housing is one of Australia’s most wicked problems, and industry and governments at all levels are committing significant resources to address chronic shortages.

In this presentation, the Institute of Regional Future’s Director of Research Programs, Amanda Wetzel, provides insights into the global nature of this problem. It is imperative that we broaden the current narrative around land use and supply, to the need to establish a holistic system that connects housing, infrastructure and place across the spectrum of government and industry.

The content of this work was presented at the third Hunter Insight Series, presented at the University of Newcastle in October 2023.

Summary

This presentation outlines the profound housing crisis currently faced by Australia and the critical need for systemic reform. It draws parallels between the Australian situation and international responses to the global housing crisis. By examining historical initiatives, the presentation highlights the continuity of housing challenges throughout the years. The inefficiencies in the existing housing planning and delivery system in New South Wales are exposed, emphasizing the urgent need for transformation. Key issues are 1) the misalignment between projections and targets; 2) the inadequacy of local government areas as housing market areas; and 3) the misconception that rezoning land guarantees supply. We emphasise the importance of adopting a housing market area approach, considering internal migration patterns, and embracing stakeholder engagement for adaptive management. Systemic improvements are urgently required to deliver sustainable solutions and avoid future housing crises.

Introduction

The housing crisis is a pressing concern that demands immediate attention and systemic reform. There are many challenges faced by the housing sector in Australia, but these have comparative international responses, and a long history. The existing housing planning and delivery system in New South Wales has limitations and needs transformative changes. This presentation addresses key issues, proposes solutions, and stresses the urgency of adopting a housing market area approach.

International experiences

Australia is not alone in facing this housing challenge. Governments across the globe have been taking similarly drastic measures. One such case is Ontario, Canada, where the reactions to their proposed solutions closely mirrored the discourse here in Australia. The enormity of the changes being proposed, both here and abroad, have been genuinely unprecedented.

History repeating

The housing crisis is not a recent phenomenon; it has deep historical roots. The Australian Housing Conference in 1982 serves as a case in point. A pamphlet from the conference illustrates the longevity of the crisis with a number of familiar and recurring themes raised, including:

a large backlog of neglected housing needs,

growing homelessness and reliance on marginal forms of housing,

rising interest rates excluding people from home ownership,

overcrowded private rental markets, and

long waitlists for public housing.”

Where to start?

More Government money than ever has been allocated to deliver housing…land dedications, faster approvals, infrastructure, construction skills and capacity building have been prioritised. However, before we pour billions of dollars into the system and hope for better outcomes, it’s worth pausing for a minute to check whether the system we’re all working away tirelessly within is setting us up for success.

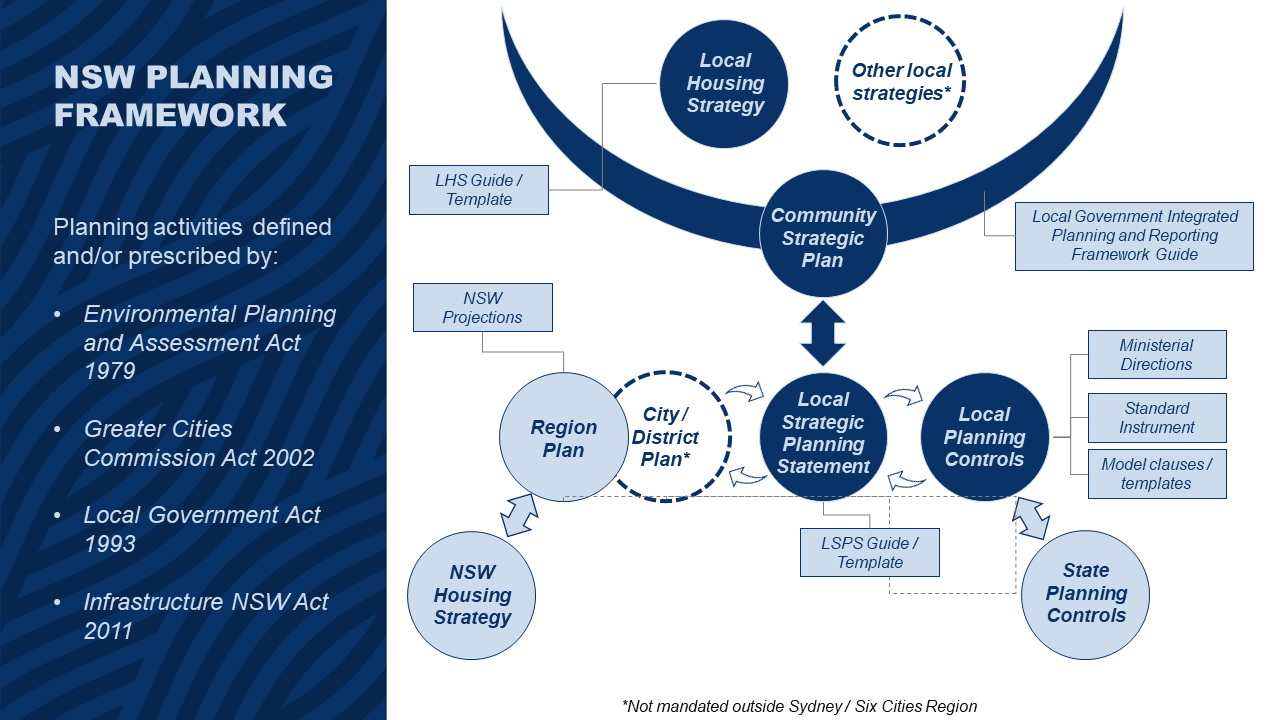

NSW Planning Framework

In practice the ‘heart beat’ of the NSW Population projections are circulated through the system by a range of policy directives. The ‘main artery’ for planning goes via Regional Plans to Local Strategic Planning Statements to be operationalised. One of the hallmark characteristics of the system in NSW is how long it takes an idea to translate into changes on the ground – which can be anything from 5 to 15 years (or more). That’s because this system is linear, complex, and relies on several interdependencies. We must ask ourselves whether this sets us up for the rapid responses to the housing crises that we urgently need?

Key Truths

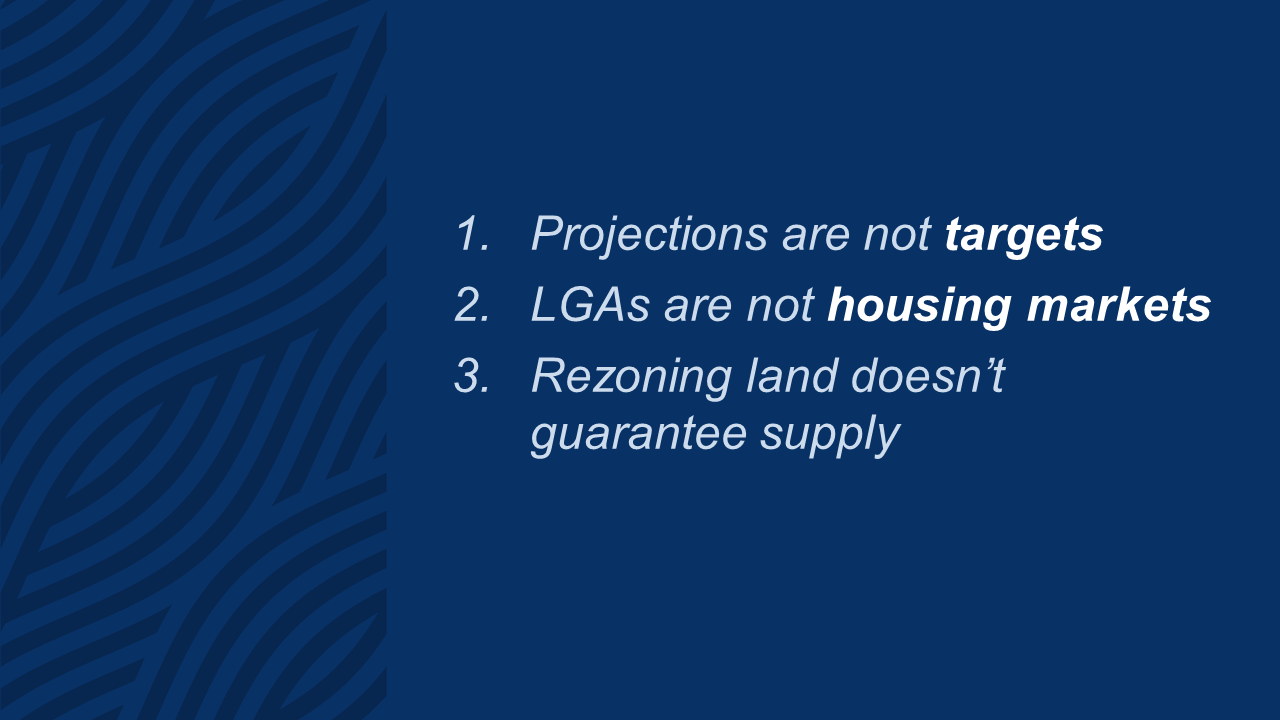

Three fundamental truths must be acknowledged for effective planning:

Projections Are Not Targets: Population projections, while vital, fluctuate over time, demanding a flexible approach to housing planning.

Local Government Areas Are Not Housing Market Areas: To understand the housing market’s needs, it is imperative to define housing market areas that transcend local government boundaries.

Rezoning Does Not Guarantee Supply: Rezoning land is only one part of the solution; adequate infrastructure and systemic support are equally crucial.

Projections aren’t targets

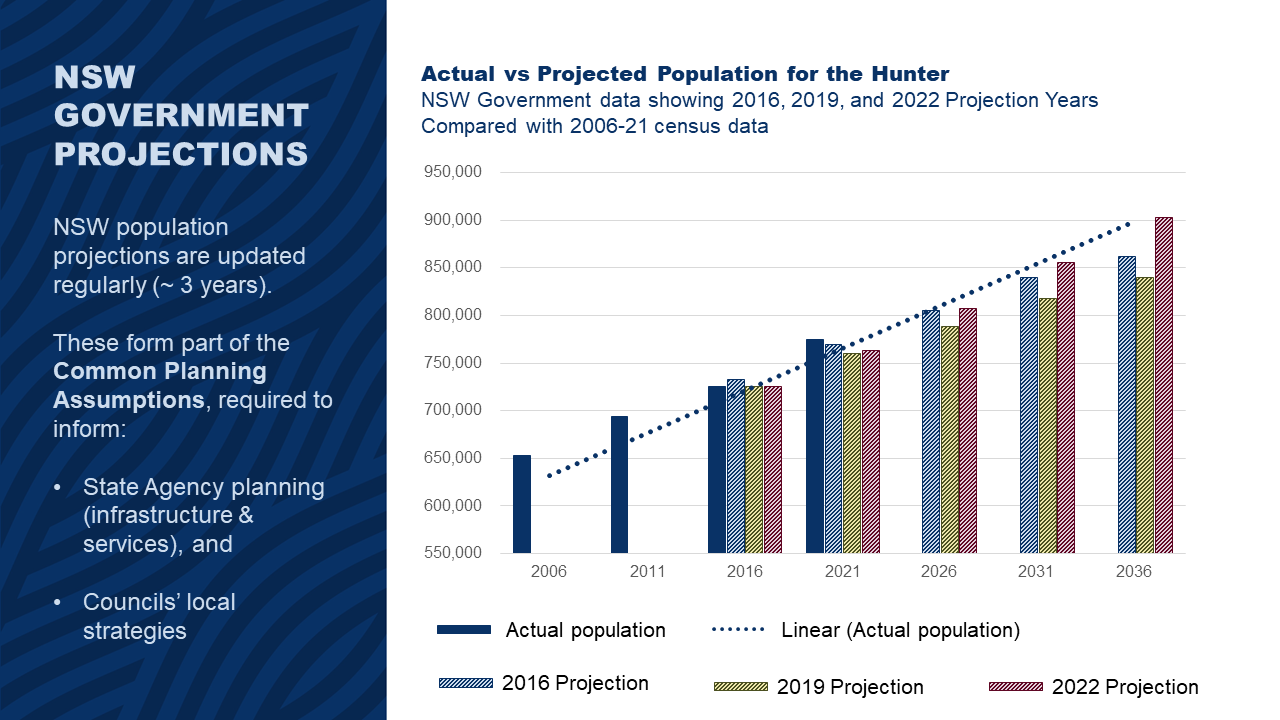

One of the key drivers of housing demand is population growth so it makes sense that the State-wide population projections, published by the NSW government, are in the planners’ toolkit. As part of the ‘Common Planning Assumptions’, the projections are required to inform state agencies’ service and asset planning, and Councils’ local strategies.

But how do these projections perform over time? The Hunter Research Foundation Centre dataset includes historic Government projections. This slide below uses those to show how the ‘growth story’ we tell ourselves about the region has changed in less than a decade. The hatched columns are the projected population levels, as updated every 3 years since 2016. Where we thought we’d grow to by 2036 back in 2019 (shown in yellow) was 63,000 people less than what was last projected in 2022 (shown in red). The solid blue tracks how the Hunter’s population has actually grown according to census data since 2006. The trendline shows how close we’re tracking against what was projected based on past performance. This indicates that it is entirely possible that we could achieve higher growth levels than have previously been projected.

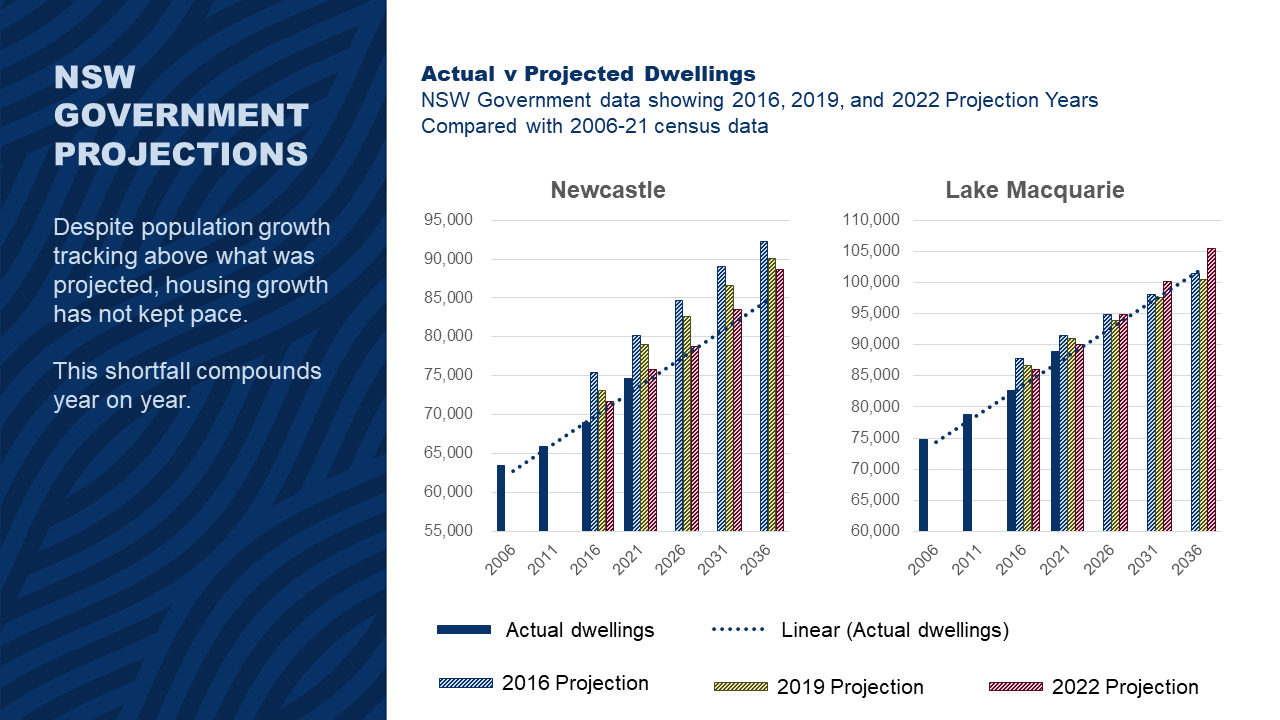

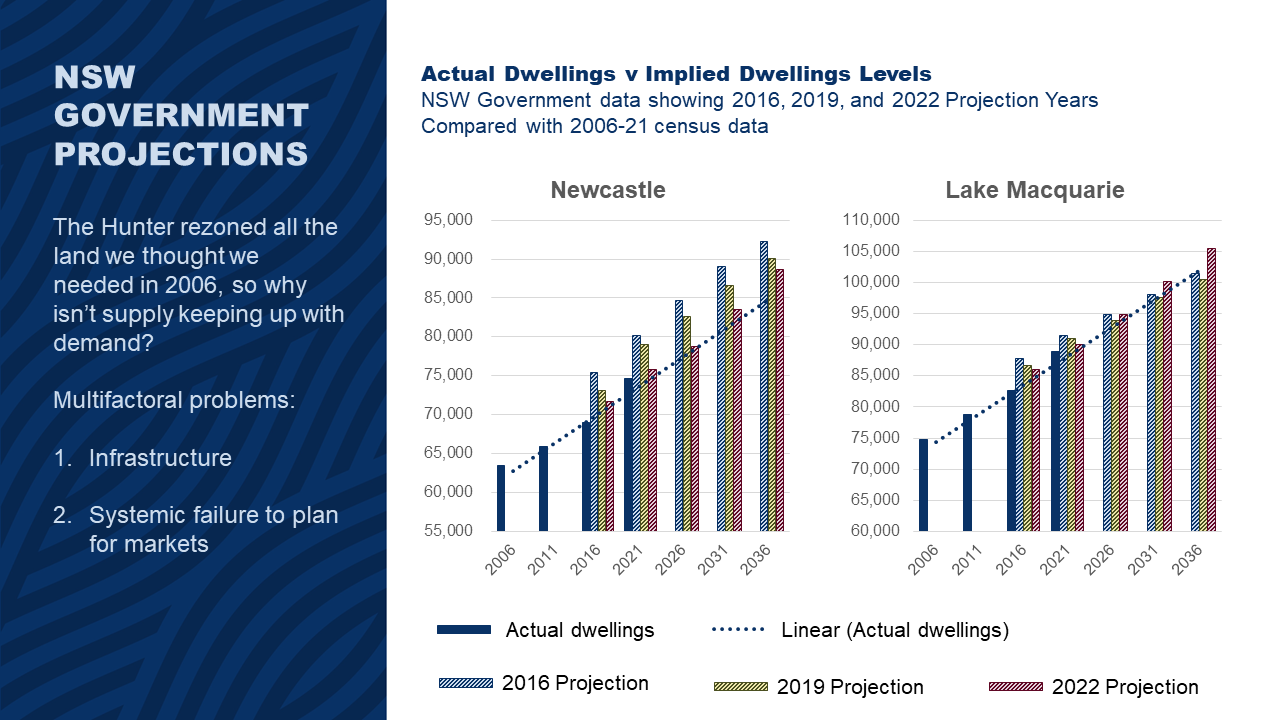

NSW Implied dwellings

Understanding how many houses we need to accommodate that growth is not easy algebra. But this is given to us in the number of ‘implied dwellings’ published alongside the population projections.

The dwellings projections are based on top down assumptions like household formation and bottom up assumptions like how much housing the existing zoned land can deliver.

This next slide singles out Newcastle and Lake Macquarie – the two largest local government areas in the Hunter by population. Like the slide before, it shows how much the projected dwellings have changed since 2016 –by around 5,000 houses in Lake Macquarie. The same data for Maitland would show a difference of around 12,000 houses. This is a fast-moving target to try and operationalise in a linear, complex, interdependent system!

Unlike the population slide before, the actual versus projected dwellings trends indicate we could fall short of the number of houses we expect to require. If that is indeed a shortfall, it compounds every year, but that growing historic deficit isn’t picked up as additional need anywhere in our planning system – the updated projections each year keep us looking forward to future need, not historic needs. So, our ‘in practice’ target is never giving us the full picture.

The next three slides help illustrate what that oversight means in the Hunter’s ‘lived experience’.

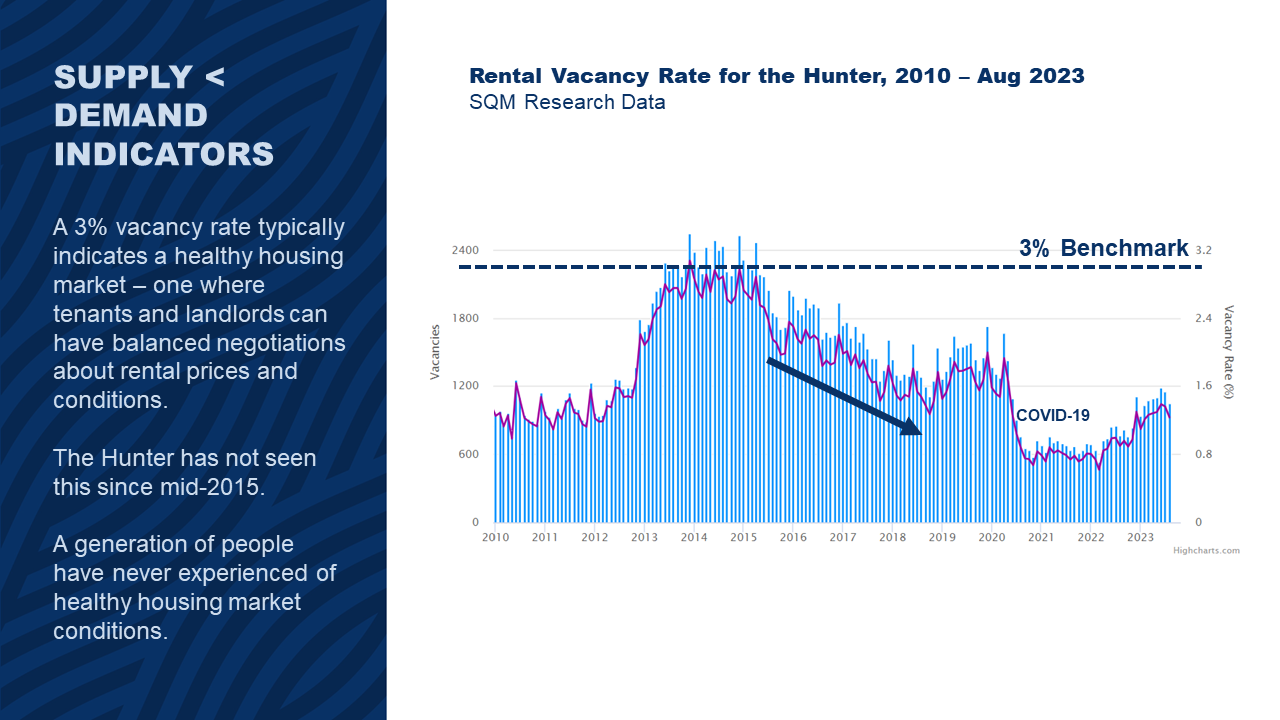

Rental Vacancy

Here we have SQM data showing rental vacancy rates going back to 2010. Typically, a 3% benchmark is used to indicate a healthy market – one where tenants and landlords can have fair negotiations about things like rent and living conditions. The data shows that while the Hunter reached up an almost touched that 3% benchmark in mid-2015, the reality is that our region has an entire generation of people who have never experienced what it is like to live in a fair and accessible housing market.

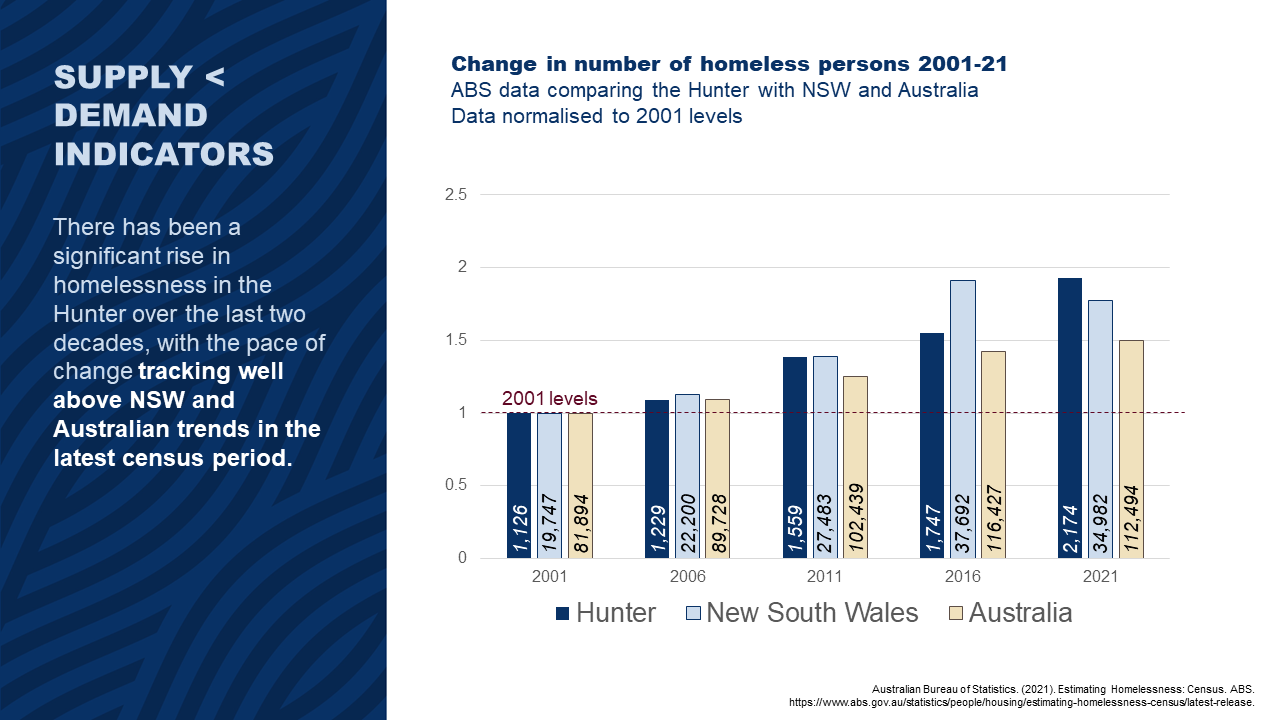

Homelessness

The next slide shows the rise in homelessness for our Region over the last 20 years. The chart is normalised to the 2001 levels for the Hunter, NSW, and Australia. It shows our Region’s rate of homelessness has almost doubled in the last 20 years. And, while the national and state levels reduced in the last census period, our homelessness rates continued to grow.

Overcrowding

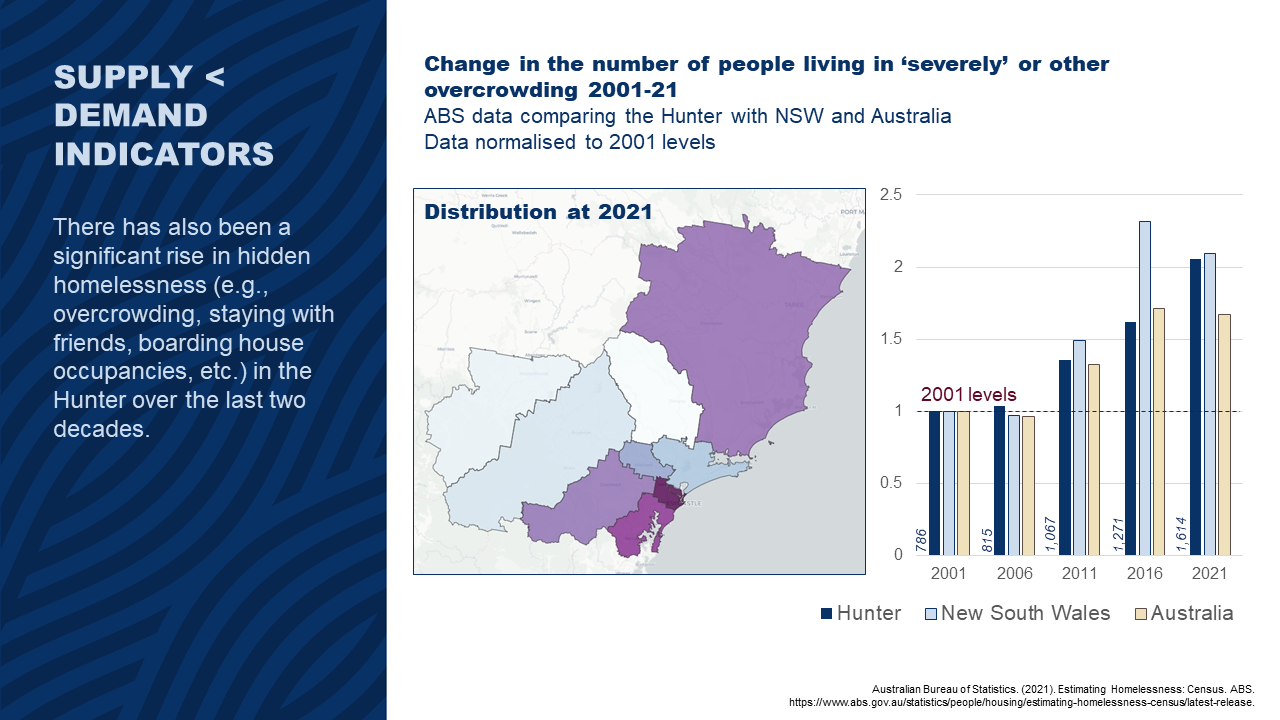

Hidden forms of homelessness are also on the rise, which looks like: crisis accommodation, people living temporarily in boarding houses or caravan parks, or staying periodically between various friends’ houses.

Here in the Hunter, we have a rising problem of overcrowding.

Typically, we would expect to find overcrowding is more common in certain segments of the population – including migrant families, students, and First Nations households. Some of this is culturally driven, but much of it is not particularly where it’s prolonged or identified as ‘severe’, which is defined in the census as – households that would need 4 or more additional bedrooms to meet their needs.

This next slide shows the spatial inequalities emerging across the Region, with Newcastle, Lake Macquarie, MidCoast, and Cessnock showing the highest concentrations.

We urgently need to move beyond relying on projections as our ‘in practice’ housing target and instead develop more robust planning methodologies with a built-in level of contingency to truly address pre-existing and future housing needs.

Local Government Areas are not housing markets

An awful lot of expectation and responsibility to deal with the housing crises falls to Councils – they’re involved in setting the planning controls, assessing and approving residential developments, and delivering local infrastructure and services.

But allocating a portion of growth to a local government area doesn’t give us the full picture of what ‘the market’ needs, because local government areas are not housing markets.

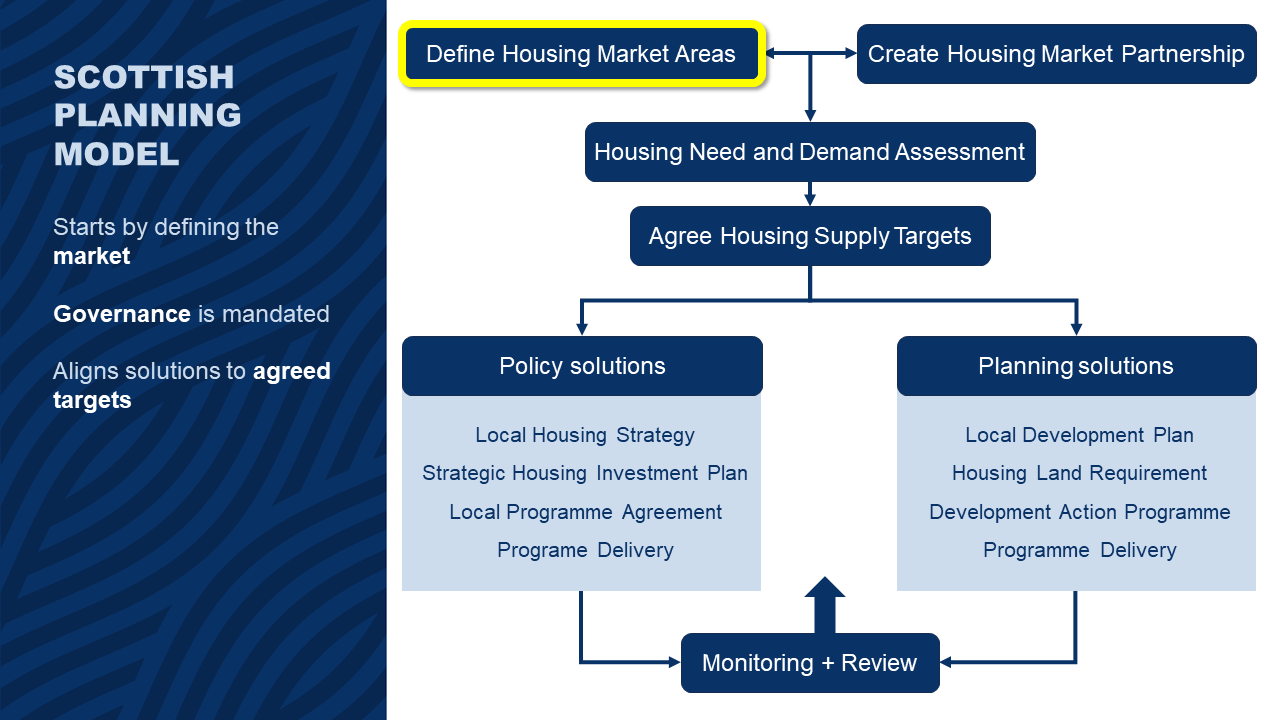

Scottish Planning Model

If we’re going to think about whether our system is designed for success, it is worth looking at other approaches. Given the almost global experience of a housing crisis, we can’t point to anywhere as ‘best practice’. But if we’re going to rely on localised approaches, we can look at systems like Scotland’s for lessons.

Key to this approach is…that it starts by defining local housing market areas, to set the frame for strategic planning and policy setting. From there, it mandates a governance arrangement to determine needs and agree targets, before operationalising these through policy or planning controls.

Defining a market for a good is about understanding where a level of price uniformity exists in the context of transport cost. The difference being that in ‘goods’ markets, it is the product is that moves… but in a housing market, it’s the people that move.

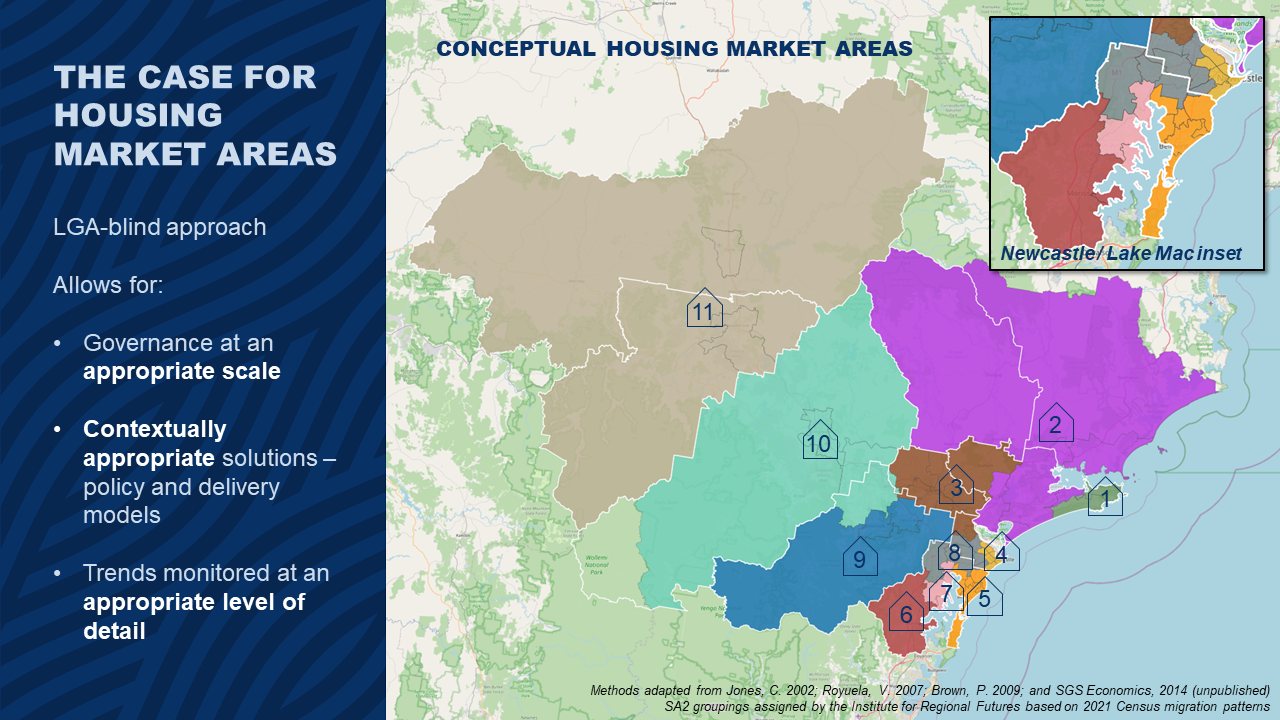

So, here at the Institute, we’ve been playing around for the last several weeks to draw on examples from literature and practice, including guidelines from the UK and housing studies by SGS here in Australia to try and re-imagine a different spatial framework that might help us understand housing market needs more robustly.

Case for housing market areas

We rely so heavily on journey-to-work data in planning, but it is evident across Australia that centres-based planning is become less relevant due to the decentralisation of jobs and rise of more ‘From home’ options to access goods and services (think home schooling, Amazon delivery, and Uber Eats).

Looking at buyer/renter behaviour we know that people aren’t necessarily tethered to the address of their employer. It’s a complex and often highly personalised choice model …just think about your own motivations the last time you moved – was it:

- To get into your preferred school catchment?

- To be closer to your parents?

- To get closer to the beach?

And here in the Hunter, many households have traditionally opted to locate themselves between more than one centre to meet their specific needs – for example much of Maitland’s growth has been attributed to dual-income households with one person working in mining in the Upper Hunter and the other in health or education in the Lower Hunter.

So rather than journey to work, we drew from internal migration patterns using data from the last two census periods. That allows this map to tell us where people who are already local and need to change their house (but not uproot their whole lives) are more likely to search to meet their need.

This approach is different from the journey to work approach because it is likely to reflect more of the social, price-tag, and place-attachment drivers influencing people’s decisions about where to live.

The different colours show these migration-based ‘housing market areas’, and the white lines are local government area boundaries. This modelling showed time and again that in reality, people’s choice about where to live doesn’t stop at LGA boundaries.

The place-based solutions we urgently need to address the housing crises must be grounded in action, not just aspiration. Taking a housing market rather than LGA approach do this would make more sense by allowing:

- Data to be collected and analysed at a level where the trends make sense in relation to the research questions you want to ask,

- Governance to happen at an appropriate scale, and

- Solutions (be they policy or planning) to be suitably contextualised.

This configuration still needs some testing (and some more modelling in the MidCoast area), but we can already see a few advantages to the approach.

Just picking up on Maitland in brown – mover behaviour shows a preference area reaching into both the Newcastle and Port Stephens local government areas and, I would hypothesise, the southern parts of Dungog around Clarence Town if we went more granular than the underlying SA2s we used as building blocks allowed.

We believe using these areas to frame housing needs assessments and governance arrangements would be far more effective than our current approach but putting this approach into practice, however, would require government funding and attention.

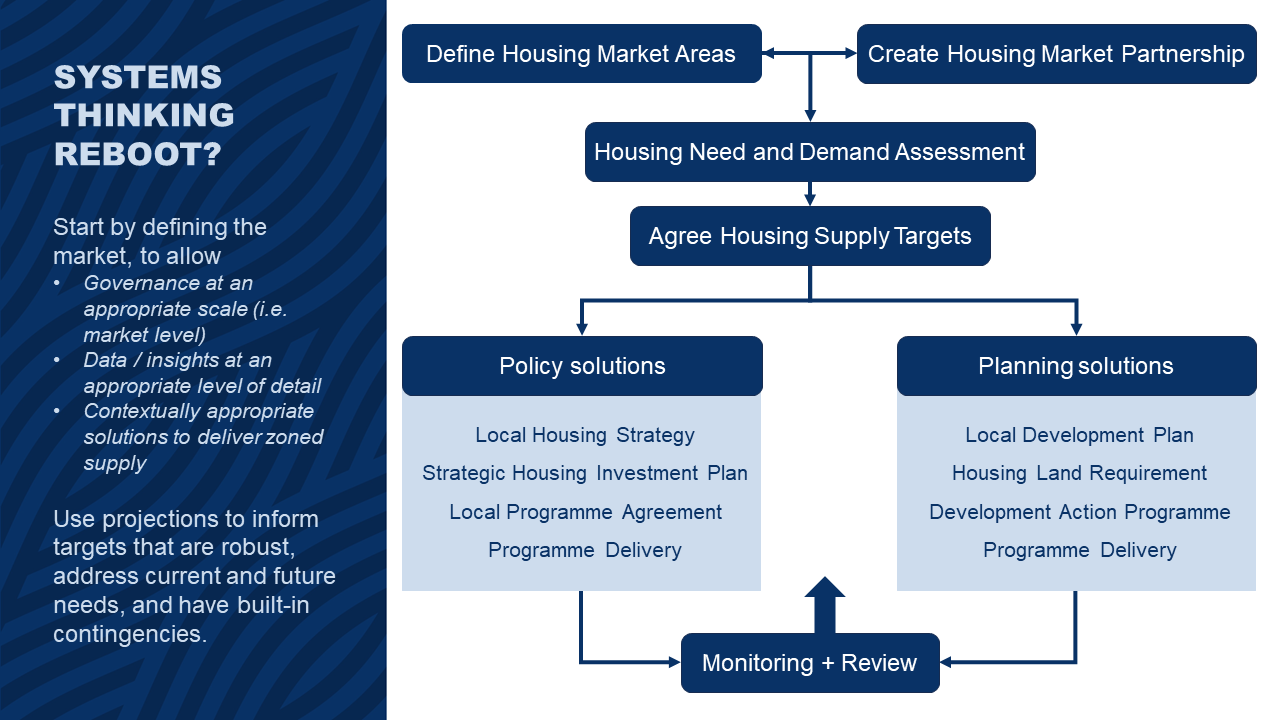

I would argue this type of systems-based improvement is just as urgent a priority as addressing our infrastructure backlog if we truly want to deliver sustainable solutions.

Actual v Projected dwellings (again)

Why aren’t we able to supply in line with market demands?

Of course there is a problem with delivering the infrastructure new projects need – There has been a lot of media coverage recently on the cost of infrastructure to service new growth fronts, particularly in Western Sydney and the outer edges of Melbourne.

But this has been a Hunter-specific problem for decades. Misalignment in the funding and delivery of infrastructure – for a long period of time the issue was with Hunter Water’s trunk infrastructure, and more recently the literal roadblock is proving to be Transport for NSW.

Learning from that example, it was the organisational re-think that occurred within Hunter Water that made the difference in so far as they accepted their role in the Region’s growth story and repositioned their own strategic planning capacity and capabilities to do things differently. This is a lesson for all Government agencies responsible for assets that enable new housing projects to go ahead.

But, beyond infrastructure, there is a bigger, more systemic failure which is that we aren’t planning in the right way to truly deliver place-based solutions. We don’t even know the full picture of what we need to operationalise.

So, does it make sense to push billions of dollars of public sector money through this system and expect to achieve the results we need?

Where to from here?

Taking the time to work on the system now, and pivot into a more stakeholder engaged adaptive management approach, will better set us up for success moving forward.

So, as we embark on an unprecedented level of spending to deliver the housing Australia needs, we call on Governments at all levels to use at least some of that on system improvements now to avoid standing here in another 40 years, recalling the 1982 Australian Housing Conference’s harrowing scope to current crisis in the housing sector.

Delivered by the Institute for Regional Futures, the free Hunter Insight series provides data and analysis compiled by the Institute’s research team addressing social, economic and spatial challenges facing key sectors. The Institute partners with all levels of government, and with industries and communities to build the evidence-base needed for sustainable planning and delivery for regional communities. For more information about the Institute and the Hunter Insight series, please visit https://www.newcastle.edu.au/research/centre/regional-futures